The letter S appears nowhere in the word “dollar”, yet an S with a line through it ($) is unmistakably the dollar sign. But why an S? Why isn’t the dollar sign something like a Đ (like the former South Vietnamese đồng, or the totally-not-a-joke-currency Dogecoin)?

There’s a good story behind it, but here’s a big hint: the dollar sign isn’t a dollar sign.

It’s a peso sign.

Bohemian Rhapsody

Though the dollar and peso symbols are inextricably linked, the origin of the word “dollar” is rooted in elsewhere. Its story begins in 1500s Bohemia, a central European kingdom spanning most of today’s Czech Republic.

Central Europe had just become rich with silver. After centuries of sending its silver (and gold) abroad in trade for consumable luxuries like silk and spices (very little of which ever found its way back), new sources of silver ore were discovered in Saxony, German Tyrol and Bohemia. With far more silver than still-scarce gold, Tyrol began replacing its teeny-tiny gold coins with big heavy silver coins of equal value. The newly-minted guldengroschen coin, 32g of nearly-pure silver, was an instant hit.

Fast forward to 1519. The Kingdom of Bohemia’s Joachimsthal region was finally producing enough silver to begin minting a heavy silver coin of its own. This new Bohemian joachimsthaler coin improved on the guldengroschen, adjusting the weight and purity slightly to make the coin evenly divisible into existing European weights and measures. It rapidly became the new European favorite, and soon most anyone with silver was minting their own version. The –thaler suffix came to refer to any and all of these similar heavy silver coins . . . and over the next few decades the thaler coins came to have several transliterated variations on their names: the Slovenian taler, Dutch daalder, and in English, the word thaler became dollar.

A Whole New World

Central Europe may have been flush with silver by earlier standards, but by the 1530s the mines were already slowing down . . . and all their riches would be utterly eclipsed by what Spain had just found in the New World. Between melting down the silver of conquered civilizations and heavy mining for more, for the next three hundred years 85% of the world’s silver production would come from Spanish-controlled Bolivia, Peru, and Mexico.

While other nations had been sporadically reducing the silver content of their once-nearly-pure thaler/daalder/dollar coins, Spain suddenly had more silver than any other nation on earth, and therefore no reason to ever debase their country’s coinage. And the seemingly unending flow of silver meant they could mint a lot of those coins, too.

Blessed with both quantity and stability, the Spanish real de a ocho coin (commonly known as a peso de ocho or “piece of eight”) gradually supplanted all competing thalers as the coin of international trade. Before long, the “Spanish dollar” was being used everywhere from the West Indies to the Far East.

For a feel for just how widespread this single Spanish coin really was, just look at the names of a few national currencies used today:

- Eight countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Philippines, and Uruguay) call their currency the peso,

- China and Japan’s respective yuan and yen currencies are named for the round shape of Spanish pieces of eight (on which the first yuan coins were modeled),

- The riyal of Saudi Arabia (and therefore the Saudi-based Qatari riyal as well) got its name from the Spanish real, historically represented in the region by the peso de ocho coin,

- And when it came time for the newly-formed United States of America to create their own currency, they chose to name it the dollar, after the Spanish dollar coin (the most circulated coin in the country at the time, and for a surprising number of years after as well.) This was the first formal use of “dollar” as a base currency instead of a single coin, but the trend caught on, and the dollar is now the base currency of 37 nations and 9 territories.

Yes, so influential was the silver “piece of eight” that 32% of the world’s population live in countries with currencies named for, or originally patterned after, that single Spanish coin, including the modern U.S. dollar.

P.S. I Love You

Most of our modern symbols owe their existence to the tediousness of handwriting. Writing things by hand was slow (and boring), so scribes would look for ways to speed (and liven) things up.

As one example, the ampersand (&) began its life as the Latin word “et” (meaning “and”) . . . first as a stylized ligature where the two letters were connected, eventually resulting in a single conjoined symbol. The “at symbol” (@) probably got a similar start, although nobody’s entirely sure what was originally abbreviated for that one.

As previously noted, the peso de ocho was the go-to currency for international trade. Anyone frequently conducting trade was likely conducting much of it in pesos, and would then be stuck writing the word “pesos” on their ledgers, over and over and over and over. Which would have been boring, and also needlessly wasteful of both time and ink.

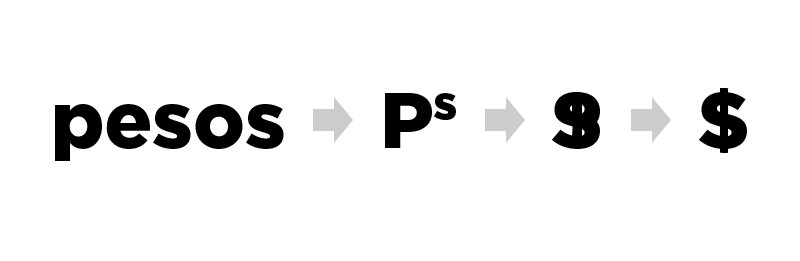

So merchants devised a simple and obvious shorthand: “P” for “peso” (when plural, “Ps”). It could have ended there, but some (I assume they were just bored) merchant(s) thought it would be even cooler to write the P and S on top of each other. This apparently caught on, and by the 1770s they had dropped the bowl from the P entirely, reducing the shorthand to an S crossed with the vestigial stem of what once was a P. And thus was born a brand new symbol, still used to mean peso today: the peso sign ($).

And because the US dollar was named after the Spanish peso de ocho “dollar” coin, the same peso symbol was ultimately used to refer to pesos and dollars both.

And that is why the dollar sign is an S with a line through it.

Edit for credit: final diagram inspired by Wikimedia Commons/Davodd.

This article originally appeared on the Observation Deck.