Two hundred years ago, Christmas Day in the USA came and went with barely a mention. There were no special family gatherings, no big dinners, no presents, no tree, no stockings or stories of Santa Claus. Outside of certain German and Dutch communities, there were effectively no special church services, no nativity scenes, carols or bell-ringers. Though there were still scattered private observances, Christmas was essentially nothing, a non-event.

This hadn’t always been true. In earlier centuries, plenty of American colonists had celebrated Christmas. Traditions varied, from quiet religious services to rowdy, days-long parties full of feasting, drinking, gambling, and theatrical performances (imagine a cross between New Year’s Eve and Mardi Gras) . . . but by the 19th century, American Christmas had simply disappeared.

How The Brits Stole Christmas

Plenty of Americans had also not celebrated Christmas. It wasn’t the main Christian holiday (that was Easter), its entanglement with pagan pre-Christian winter festivals was pretty well known, and everybody knew that December 25 wasn’t really Jesus’ birthday anyway. To the Puritans of New England, Christmas was just Catholic superstitious nonsense (several New England cities and states even outlawed the holiday), while many other denominations let it pass unobserved.

(Also the non-Christians and Native Americans probably didn’t care.)

But in the Dutch and German settlements, and especially in the English Anglican communities, Christmas was embraced and celebrated as both a religious and a (rowdy) secular holiday for many years.

And then the Revolutionary War happened.

The long, brutal, and bitter war with England destroyed American affection for a whole host of things considered “too English”. Tea, for example, was wildly popular across the colonies until the 1770s. But thanks to the war (and a decade-long boycott of the English-controlled East India Company) Americans switched to coffee en masse, trading the beverage of King George for something a little more patriotic (even if they didn’t really like the taste).

Christmas (celebrated so enthusiastically by Anglicans) became another casualty of the fresh American disdain for all things “English”. By the time the new Constitution had been sorted out, there was no reason not to hold Congress on Christmas Day because nobody in Congress had any plans to do anything else. To the newly-forged United States of America, Christmas was largely forgotten.

Santa Claus Conquers The Americans

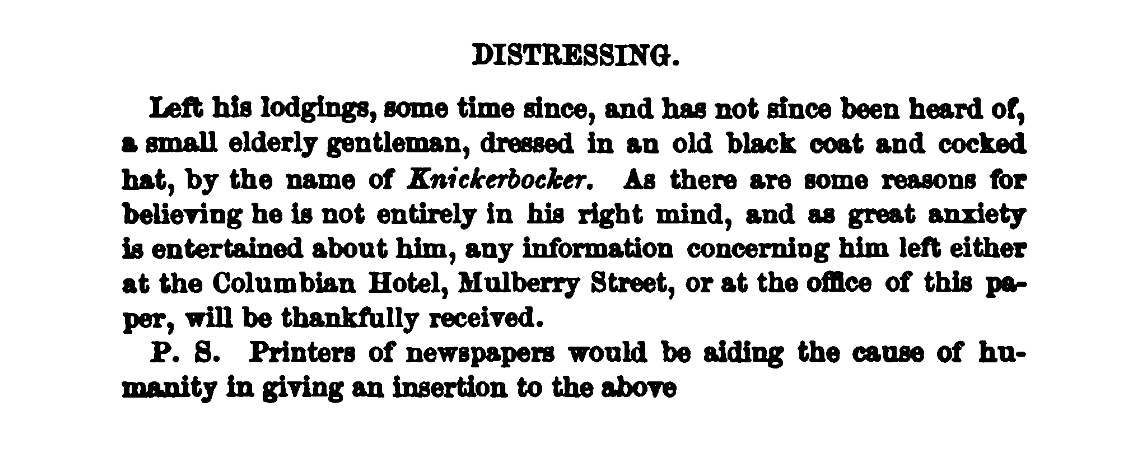

In October of 1809, the following missing persons announcement ran in the New York Evening Post:

Except . . . there never was a Knickerbocker. The historian, the newspaper notices, the hotel debt, and the “manuscript” were all the crafty invention of Washington Irving. His “History” was pure satire, and thanks to its humor and its widespread popularity, it made a lasting mark on American culture. (Just ask the New York Knicks.)

A parody of Dutch and New York culture, A History of New-York took some creative liberties with the Dutch Sinterklaas (the Dutch name for St. Nicholas). Flying over the trees in a wagon, pulling gifts from his pants pockets and tossing them down chimneys every December 6 (the real-life St. Nicholas day), Irving’s “Santa Claus” was totally new invention, with no real precedent (other than name) in any existing traditions.

And this brand new Santa was incredibly popular.

By 1814, at least one book was reminding children that “Old Santa-claw” wasn’t really real. By 1821, his “wagon” had become a sleigh pulled by reindeer. People loved Santa Claus, and in poem and song, picture and verse, Americans were collectively writing his backstory, building his mythology, and developing new traditions around him.

I’m Dreaming Of A Fictional Christmas

America was rapidly transforming. Technological improvements in transportation and communication were connecting people in new ways, immigration continued to shake up loose notions of “American” identity and culture, and national industry was growing at breakneck speed, a necessity when America was effectively cut off from trans-Atlantic trade in the War of 1812.

That same war was rough on the Irving family overseas import-export business. So in 1815, Washington Irving sailed to Liverpool to help his brother rebuild the firm.

Rather than return with his tail between his legs, Irving stayed in England, hoping against historical odds that he might be the first American to earn a living by writing. While looking for creative inspiration that might interest his American audience, and between producing such hits as Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Irving read a 160-year-old English pamphlet defending Christmas.

(Waaay back in the mid-1600s, after executing King Charles I, Oliver Cromwell’s Puritans had, for several years, outlawed the celebration of Christmas in England. The pamphlet was the work of a dissenting royalist.)

Mingling the centuries-old anti-Puritan tract with his own imagination, Irving described for his American readers in five parts a (fictional) “traditional” English Christmas. Writing about cozy fires, crisp weather, heart-stirring music, yule logs, pie, family, friends, games, joy, gift-giving, children, merriment, and domesticity, Irving related (and invented) Christmastime “traditions” that might perhaps insulate their practitioners from the impersonality, coldness and cruelty all too common to “modern life.”

Irving’s Christmas essays attracted plenty of American interest, but it was his good friend Clement Clarke Moore who brought all the pieces together. Published anonymously only a few years after Irving’s Christmas essays, Moore’s A Visit From St. Nicholas combined Irving’s vision of a happy, family-oriented Christmas with Irving’s wildly-popular “Santa Claus” character.

Newspaper after newspaper quickly reprinted Moore’s poem. It went completely viral. Within a decade, A Visit From St. Nicholas was known throughout the country, and between Irving’s essays and Moore’s poem, Christmas was back in a way it had never been before. Gone were the raucous Mardi-Gras-like parties, the in-the-street brawling parties. People all over America were finally celebrating Christmas—Washington Irving’s fictional “traditional” Christmas—”as if they had been doing it all their lives.”